These are the ten greatest films ever made. Most lists like mine also have these movies at or near the top, and for good reason, because they are the greatest. They are all technically genius, significant in time and place, and help us enter other unseen worlds. See these films as fast as you can, then see them again. There are some on this entire list that you’ll see and not enjoy, or wonder why its on the list, but like most things, context is everything. Be an active participant in each movie you see, and you’ll begin to see things differently. We create stories based on our lives, then those stories become the narrative lenses we see life through. The greatest narrative is out there—seek and you shall find.

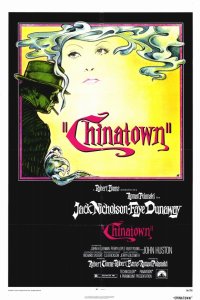

—This may well be the greatest screenplay ever written. It’s extremely smart, perfectly-paced, highly visual, and nothing goes unused. Robert Towne gives us a perfect example of film noir, but it plays in a way that the central characters are not simply agents, or victims of their own doing, but victims of the powerful sins of the community. Chinatown has a single through-line that binds the whole story—”You have to be rich to commit a crime.” Those with power will do everything in that power to retain their power. Morality is defined by those in power, and what may be immoral, illegal or disgusting for the common man to partake in, is not only acceptable for those with power, but wholly justified. The story here is enveloped by a reality that ought to outrage us, but doesn’t because we either believe we are powerless, choose to be apathetic, or realize that we are the ones in power. Winner of 1 Academy Award.

Directed by Roman Polanski, 1974. Starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway.

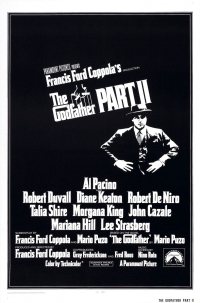

—The follow up to the greatest gangster film ever is darn close to being better than the original. Al Pacino is stellar here as the new Don Corleone, carrying over every nuance from the final shot of Part I into his Part II performance, and Robert De Niro is standout brilliant as the young Vito. It is a startlingly different film than the first, but equally tragic. It is one of the most astonishing pieces of dual-story filmmaking ever created, as Coppola weaves a compelling father/son parallel, engrossing not because the narratives need each other, but because they so often don’t, and we wish they didn’t. That they do takes each individual tragedy and places it in the context of the larger generational narrative, creating a complex comment not only on the lives of these individuals, but on all of our collective narrative. The sins of the father become the sins of the son. This is still (easily) the greatest sequel ever made. Winner of 6 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, 1974. Starring Al Pacino, Robert Duvall and Robert De Niro.

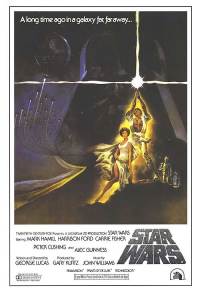

—Star Wars is perhaps the most influential pop-culture film phenomenon of all time. I only say perhaps because who likes dealing in absolutes? It’s the most influential. This is absolutely essential viewing for all human beings. The story is the epitome of the “Hero’s Journey,” featuring all the elements of classic hero mythology from age to age. The reason we identify with it so much is because of these classic hero themes. This is not just the stuff of novels and movies, but hero mythology is identifiable in all of life. We yearn for transformation, physical and spiritual; a death and resurrection; moving from one thing to something greater. It is good elevating to great in order to triumph evil. And here’s possibly the most important aspect of all—John Williams’ brilliant musical score is one of the greatest, most recognizable pieces of music not only in film history, but among any music ever written and recorded ever. Ever. Winner of 7 Academy Awards.

Directed by George Lucas, 1977. Starring Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher and Alec Guinness.

—This film is so remarkably complex, that upon first viewing it seems too simple. And it is. But it’s also tremendously complex and richly layered. Released in 1939, with Europe on the eve of the Second World War, this farcical look at the sexual gamesmanship of the French aristocracy was originally reamed by critics and audiences. I’ll refer you to Roger Ebert’s review of the Criterion DVD release of the film for a much more detailed look at why this was the case, and what makes the picture so tremendous in retrospect. The film was way ahead of its time, taking seriously its role as both art and entertainment. It’s a film by a director who rightly recognized his satire as tragedy and his tragedy as satire, standing as an intricate parable in the midst of both pro- and anti-Nazi sentiments prior to the occupation of France. All this marks it as easily one of the greatest films ever made.

Directed by Jean Renoir, 1939. Starring Nora Gregor, Roland Toutain, Jean Renoir and Marcel Dalio.

—I’ve thought hard about how to describe what is great about this film, and as great as the sequences are, and Peter O’Toole is, the things that stand out to me about this movie are single shots. Peter O’Toole blowing out a match, lavish shots of the desert landscape, a single shot overlooking the hundreds of extras in the raid on Aqaba. This movie sears itself into your mind. There are shots and scenes so spectacularly visionary that they rate in the upper echelon of anything ever captured on celluloid. If you ever get a chance to see this on the big screen it will change your life. That’s not a hyperbole. Winner of 7 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Directed by David Lean, 1962. Starring Peter O’Toole, Omar Sharif, Alec Guiness and Claude Rains.

—This film is so burned into the collective pop-culture conscious of America (and film culture in general), that to see it once is to sense its already potent familiarity. There are lines of dialogue that we have all heard, that we all know and use, and have no idea where it came from. Chances are really good it came from this movie. This wartime national anthem, though, is the ultimate Hollywood paradox. Michael Curtiz was a very respectable director, but not amazing, the film was churned out very quickly, and usually when a movie has 6 writers it is a total disaster. Yet, this is a glowing masterpiece planted firmly on the Mt. Rushmore of cinema. “Here’s looking at you, kid.” Winner of 3 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Directed by Michael Curtiz, 1943. Starring Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid and Claude Rains.

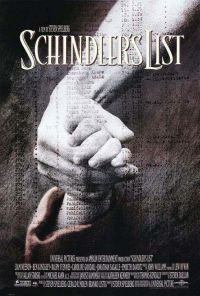

—Perhaps the most important film ever made, this is Spielberg’s most personal and powerful work. The choice between love and hate, death and life, is a delicate one, but one that becomes overpowering. Our thoughts are generally shaped by our position in the surrounding social milieu, but if we allow ourselves to see through the eyes of a human being on the other side, we are better equipped to make the decision of whether we will bring life or death, because now that other person is not just an object of our demise, but a fellow brother or sister. It is in this tension where Oskar Schindler resides, confronted with the horrifying task of doing what is right; saving life rather than taking it. “The list is good. The list is life.” Are we selfless enough to choose life over death? Because invariably, to choose our own life is to choose another’s death, and to choose another’s life is to choose our death. Are we willing to die to ourselves? “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” Winner of 7 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Directed by Steven Spielberg, 1993. Starring Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley and Ralph Fiennes.

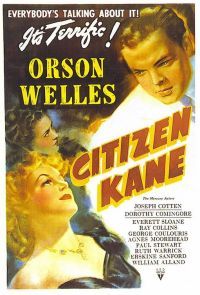

—Largely considered the greatest film of all time, and it’s hard to argue against that. Orson Welles produced, directed, co-wrote and starred in this masterpiece at the age of 25. It was a masterfully executed conglomeration of all the emerging techniques of the new sound era, which would be enough to make it a great film, but that it took all of these elements to a level that no other film before and for a very long time after could touch, makes it perhaps the greatest movie ever made. The film was so far ahead of its time (and is very much ahead of ours too), that it got lost under the weight of its own greatness for nearly a decade. Though deep-focus photography was a technique first attempted with Renoir’s previously mentioned The Rules of the Game, it is perfected here by legendary cinematographer Gregg Toland. Everything in the background and foreground is constantly in focus, forcing audiences to take an active viewership in the way Welles and Toland distort everything we think we know about our characters. The film doesn’t cut us any slack, and it doesn’t tell us how to think and feel. We are on our own, just like Kane. Watch it as many times as you can, taking note of all the little details; it’s a film so marvelously complex that it may just bring us to a greater plane of thinking about art, film and people altogether.

Directed by Orson Welles, 1941. Starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotton.

—What is it about The Godfather that consistently puts it at or near the top of every “greatest films” list? It’s attention to detail is flawless. It’s editing is benchmark setting. Nino Rota’s musical score is haunting and lingering. The atmosphere is perfectly captured in set design and costume. But the two things that make this movie uniformly considered a true masterpiece are Coppola’s carefully measured, deeply personal direction, and the barrage of brilliant performances. Coppola turns the Mafia into a genuine American family. There is not much sense throughout that these are bad people, they’re just people. Everything is justifiable. Though we see the signs of it, it is in the (brilliant is too weak an adjective) ending that we fully realize the horror of what’s happened, and can then go back and watch the rest of the film for the tragedy that it is. Marlon Brando delivers an iconic performance as Don Vito; a man content with his ethic, never apologizing for doing what he believed needed to be done. But I think it is Al Pacino who steals the film. His Michael Corleone is at once, paradoxically one of the most tragic and terrifying characters ever brought to life. Like Kay (Diane Keaton), it grieves us to empathize with the man Michael has become. This is as perfect a film as you’ll ever find, so watch closely. Winner of 3 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, 1972. Starring Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Robert Duvall and James Cann.

—The greatest film ever made, and one of the most transformative films I’ve ever seen. Highly influenced by French New Wave, Italian modernist and neo-realist, and German expressionist styles of filmmaking, the incomparable Martin Scorsese uses the editing room, his camera and lighting to phenomenal effect to create an atmosphere of self-loathing, sexual inadequacy, paranoia, collapse and redemption. De Niro turns in one of film’s greatest performances as boxer Jake LaMotta, going from a finely tuned boxer to a heavily overweight comedian, gaining 50 pounds for the role. Inside the ring, LaMotta is an animal; a violent id unleashing pent up fury on his prey. Outside the ring, he’s the exact same, he just refuses to recognize it. What makes this film so transformative for me is that through Scorsese’s guiding hand (and naturally all the other production elements) the Transcendant Spirit plays the role of active observer, waiting for that moment of release when He comes in as the reconciling force. For all of us, it takes losing ourselves to truly find ourselves. We don’t have to live in paranoia and hate, as an uncontrollable animal disregarding a latent humanity. Life is so much simpler and more beautiful when we embrace others in love. Because it is in loving others that we come to love ourselves, almost never the other way around. Winner of 2 Academy Awards, including Best Actor (De Niro).

Directed by Martin Scorsese, 1980. Starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Cathy Moriarty

What is your favorite film of all time?